[ad_1]

Juanjo Gonzalez

In early January, I wrote about winter comets with the promise to return for a broader look at the remainder of the year. Here, we’ll explore both current comets and peer ahead to see what’s around the corner. Expect some pleasant surprises.

Dan Bartlett

Comet-tracking is one of the most enjoyable of all astronomical pursuits whether you’re a visual observer or an astrophotographer. Comets have beautiful forms, evolve in appearance over time and are prone to unpredictable behavior. They also don’t sit still. To find and observe a comet night after night, week after week, brings great personal satisfaction, not only in seeing an astronomical object change before our eyes but also in the primordial pleasure of using one’s wits to hunt, find, and keep track of a moving target.

Michael Jäger

While 2022 has its share of comets, only a few are expected to reach magnitude 8 or brighter and become fair game for smaller telescopes and binoculars. I’ve included all objects expected to reach magnitude 11.5 or brighter that are visible outside of bright twilight. Of course, many new discoveries are made each year, some of which make fine telescopic or even naked-eye appearances. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) alone bags more than 200 per annum, many found by amateurs who study the publicly available images.

Robotic surveys such as PanSTARRS, the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), and the ATLAS Project discover an additional 40 to 50 objects yearly. Several times a year, amateur astronomers beat the robotic odds and uncover new comets that bear their own names. Hideo Nishimura of Japan found Comet Nishimura (C/2021 O1) last July in exposures he made with his Canon digital camera. In 2019, Crimean amateur Gennady Borisov discovered the first rogue interstellar comet, 2I/Borisov.

Now it’s time to meet our celebrity cast.

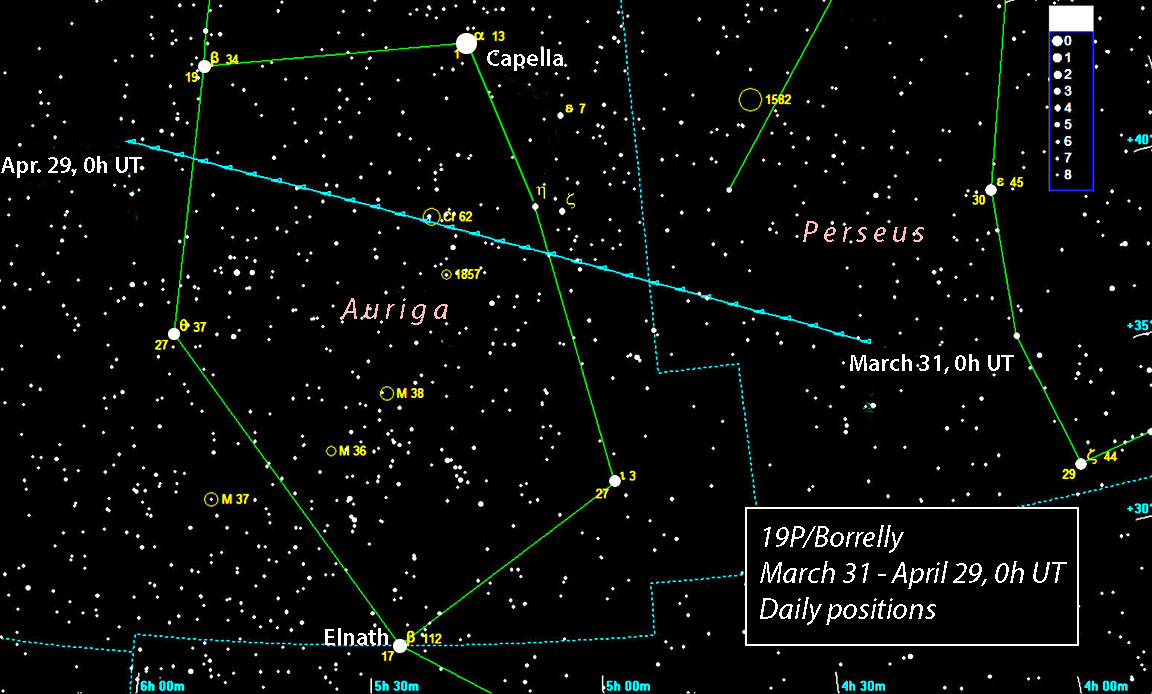

19P/Borrelly

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: Feb. 1, 2022 — 195 million km (1.3 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: Dec. 11, 2021 — 175 million km (1.2 a.u.)

Details: For many of us, 19P has been a winter stalwart at 9th magnitude, but it’s slowly faded in recent weeks and now glows around magnitude 10. On March 28.1 UT, I observed a moderately condensed 2′-diameter coma with star-like pseudo-nucleus and 6′ tail extending to the northeast in my 15-inch Dobsonian.

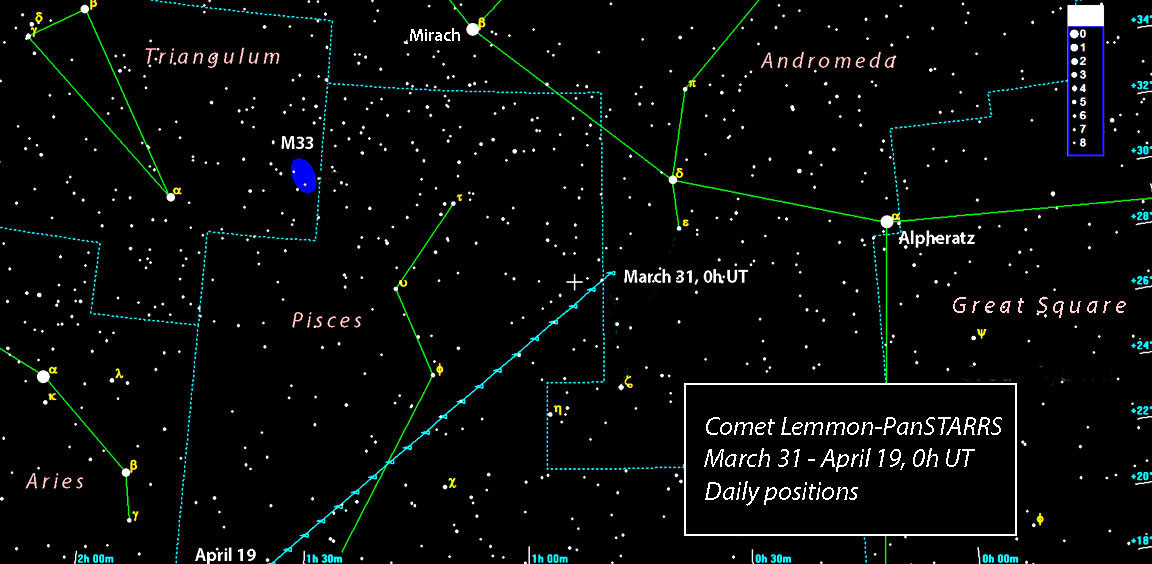

Lemmon-PanSTARRS (C/2021 F1)

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: April 6, 2022 — 150 million km (1.0 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: Feb. 12, 2022 — 210 million km (1.4 a.u.)

Details: I observed the comet at the end of evening twilight low in the northwestern sky on March 28.1 UT with my 15-inch and found it quite bright at magnitude 9.3 with a moderately condensed coma ~3′ across. Right now, it’s the brightest comet in the sky, but not for long. Lemmon-PanSTARRS is quickly approaching the Sun and will soon disappear in its glow. I found that a Swan Band filter, which increases the contrast of gas-rich comets, darkened the sky and increased the comet’s visibility and coma diameter.

Lemmon-PanSTARRS will return to the morning sky in May for Southern Hemisphere observers only, though much faded (predicted magnitude 11.5 to 12).

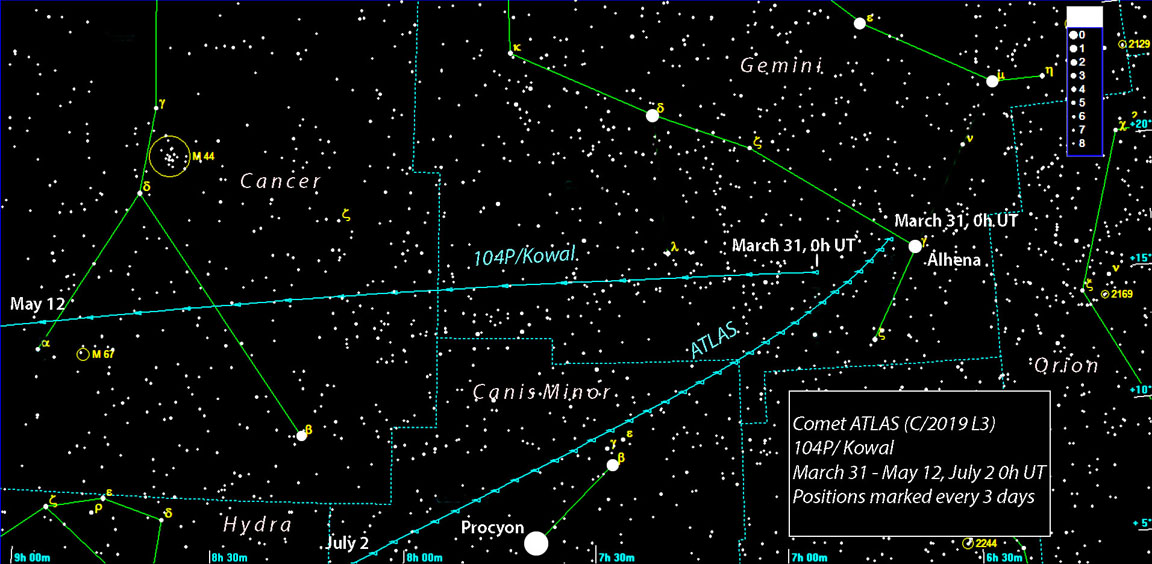

Comet ATLAS (C/2019 L3), 104P/Kowal

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion:

Comet ATLAS on Jan. 9, 2022 — 531 million kilometers (3.6 a.u.)

104P/Kowal on Jan. 11, 2022 — 165 million kilometers (1.1 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth:

Comet ATLAS on Jan. 6, 2022 — 386 million kilometers (2.6 a.u.)

104P/Kowal on Jan. 28, 2022 at 96 million kilometers (0.6 a.u.)

Details:

I’m going to miss C/2019 L3. I’ve tracked this small, tadpole-shaped comet all winter as it slowly wriggled across Gemini. ATLAS peaked at about magnitude 9.0 more than a month ago, but despite its considerable distance from Earth, it remains bright at magnitude 10 with a 2′-wide dense coma and short, faint tail pointing northeast.

Comet 104P/Kowal has been a relatively bright but diffuse object over the past several months. It topped out around magnitude 9.5 in February but has since faded to around 11th magnitude. Like Comet Lemmon-PanSTARRS it responds well to a Swan band filter.

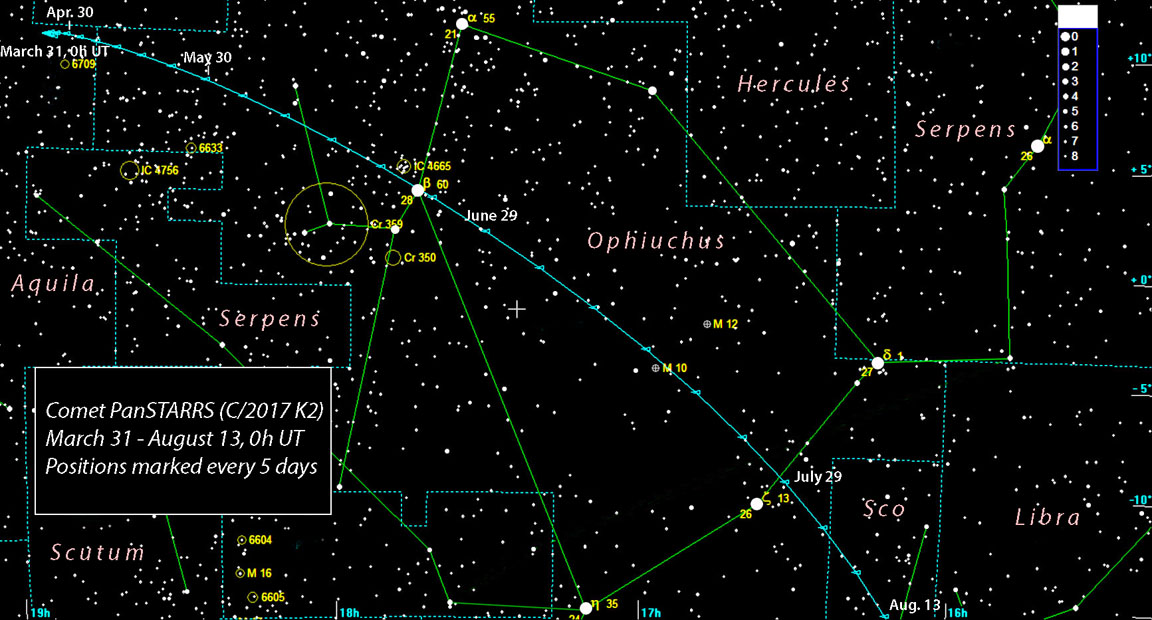

Comet PanSTARRS (C/2017 K2)

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: Dec. 19, 2022 — 269 million kilometers (1.8 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: July 14, 2022 — 271 million kilometers (1.8 a.u.)

Details: K2 has been fairly static at magnitudes 11.5 to 12.0 for months. It’s currently making a tight loop in western Aquila, traveling just 20′ east between March 31st and April 14th. Come May, it will loop back west, gradually picking up speed and brightening while plunging across Ophiuchus. Expect the comet to reach magnitude 8 to 8.5 during convenient observing hours in June and July. On July 15th, it passes ½° northwest of the bright globular cluster M10.

PanSTARRS disappears in twilight during September for northern viewers, but Southern Hemisphere skywatchers will be able to follow it through its December 7th perihelion and beyond. Although the comet will be rather low in Ara and Pavo at the time, it may reach 6th magnitude when brightest in late December through early January 2023.

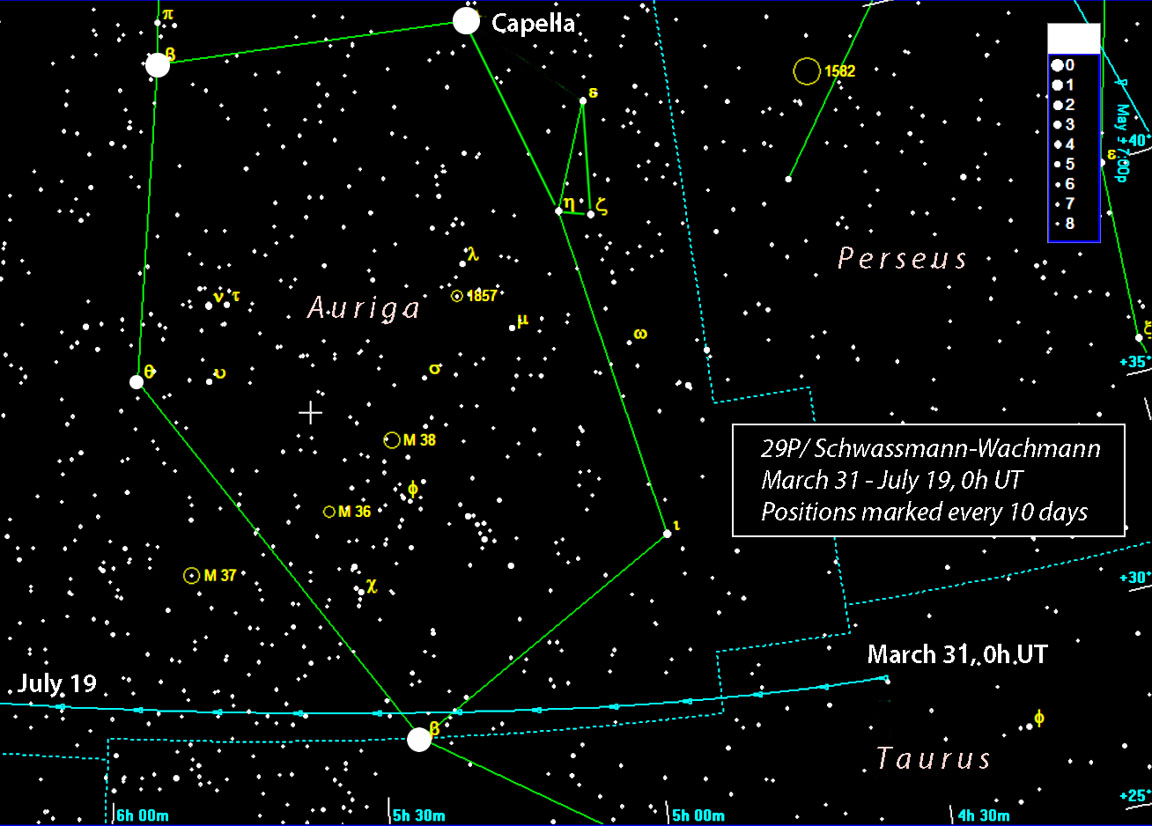

29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: April 7, 2019 — 864 million kilometers (5.8 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth (this year): 760 million kilometers (5.1 a.u.)

Details: 29P is a large and active comet with an estimated nucleus diameter of around 60 kilometers. Generally too faint to see with anything less than 14-inch telescope, it undergoes an average of 7.4 outbursts each year, causing its magnitude to vary dramatically. Most years, it shoots up to magnitude 10.5-12 at least once. At the start of a flare-up, the comet’s coma looks like a tiny bright disk that gradually expands and diffuses over the ensuing nights.

The cause of the bursts appears to be cryovolcanoes that erupt explosively after carbon monoxide and methane ices, under pressure beneath the comet’s crust, melt, mix, and release energy. Solar heating causes the crust above these spots to give way, releasing the gas along with up to a million tons of dust and debris.

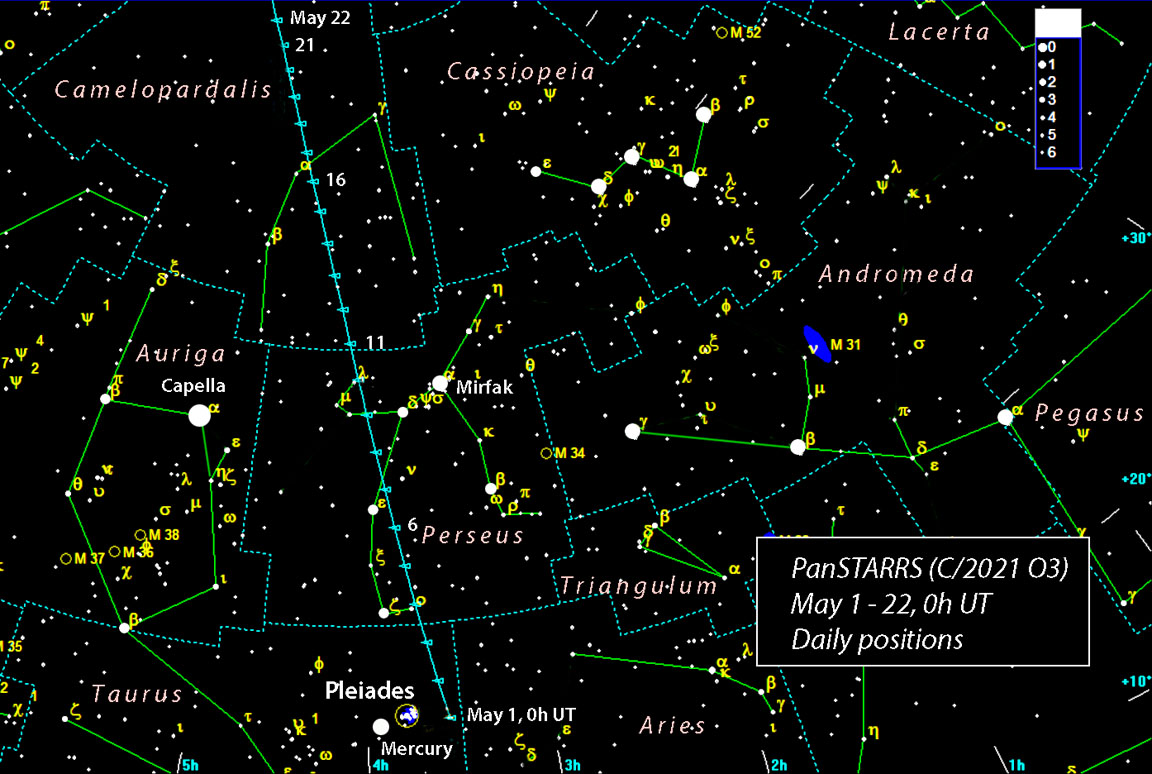

Comet PanSTARRS (C/2021 O3)

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: April 21, 2022 — 43 million kilometers (0.3 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: May 8, 2022 — 90 million kilometers (0.6 a.u.)

Details: Pinning a brightness on this icy spitball is tricky because it’s a recent arrival from the Oort Cloud. But PanSTARRS (C/2021 O3) has the potential to become a binocular comet when it passes our planet just 17 days after perihelion. If dust production is strong it could reach 6th magnitude at the start of May while hopscotching across Perseus and Camelopardalis. Lingering twilight and low altitude will present challenges at first, but PanSTARRS soon transitions to darker skies. It will be circumpolar for latitudes north of 45° on May 8.

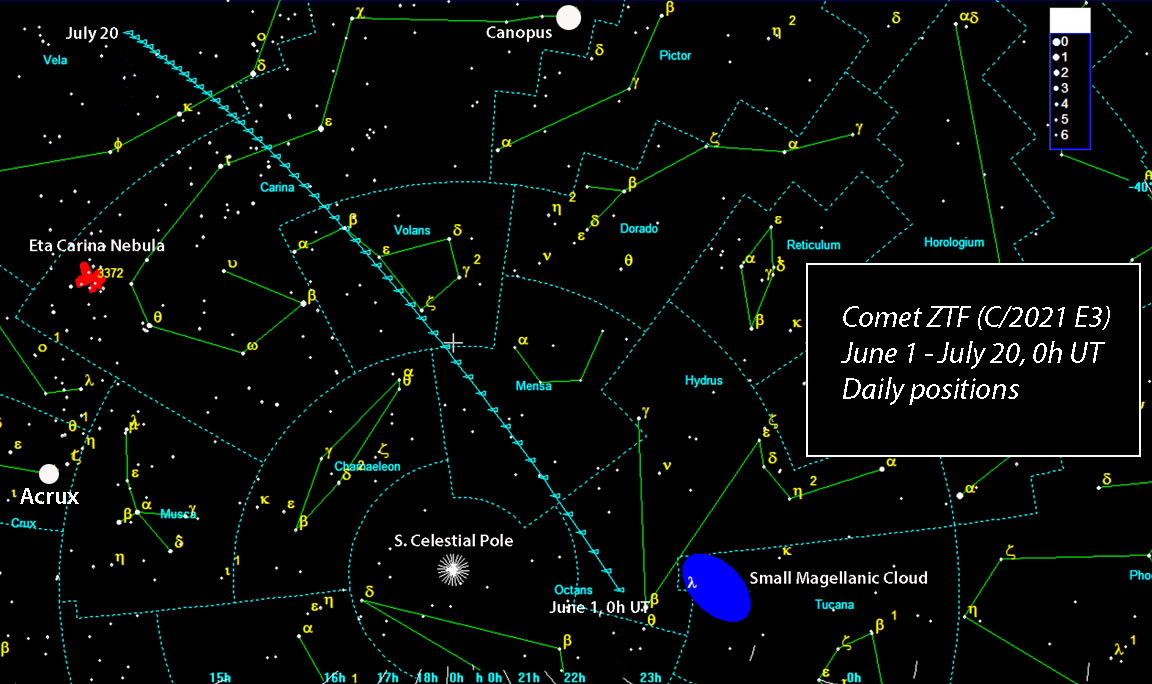

Comet ZTF (C/2021 E3)

Courtesy of Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: June 11, 2022 — 266 million miles (1.8 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: May 31, 2022 — 181 million miles (1.2 a.u.)

Details: This strictly southern comet races from the south celestial polar region into Vela from late May through mid-July.

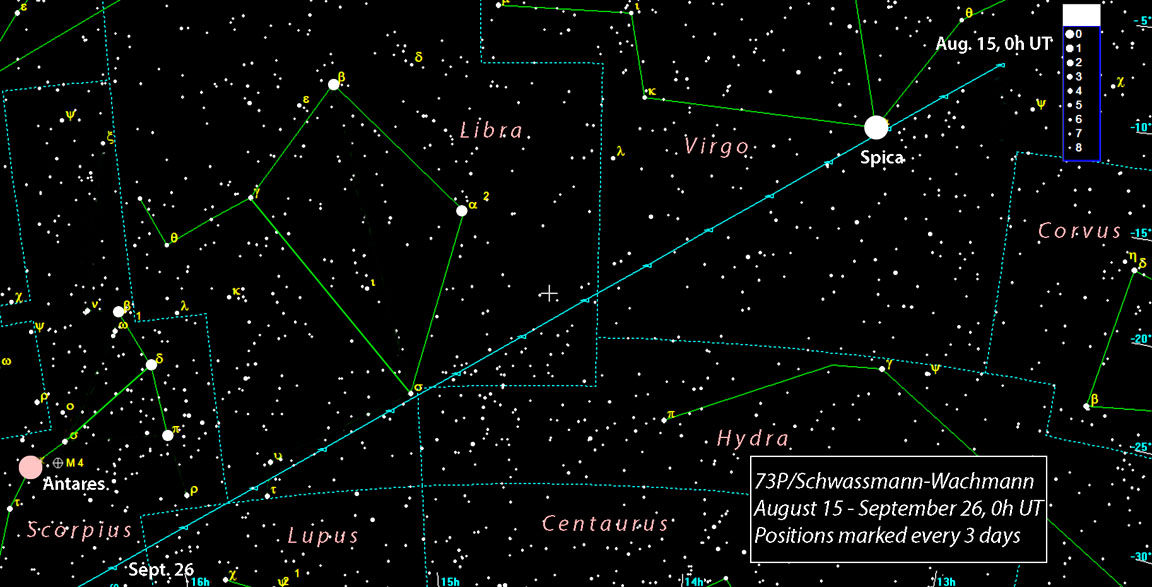

73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: August 25, 2022 — 145 million km (1.0 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: September 22, 2022 — 145 million kilometers (1.0 a.u.)

Details: 73P/S-W will be sketchy for northern observers because of its location low in the southwestern sky at nightfall from August through September. It will peak at magnitude 11.5. Southern Hemisphere comet aficionados will have a better view of what’s expected to be a dim return.

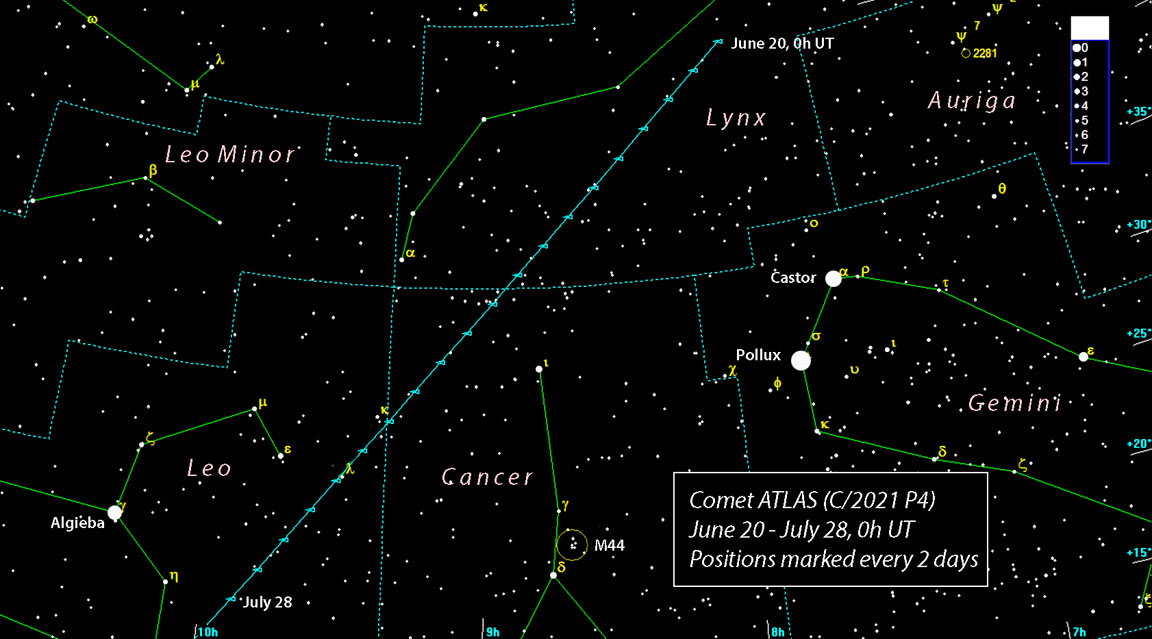

Comet ATLAS (C/2021 P4)

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: July 30, 2022 — 162 million kilometers (1.1 a.u)

Closest approach to Earth: July 13, 2022 — 293 million km (2.0 a.u.)

Details: Although Comet ATLAS (C/2021 P4) will become moderately bright at 10th magnitude, it will appear low in the northwestern sky during the best part of its apparition.

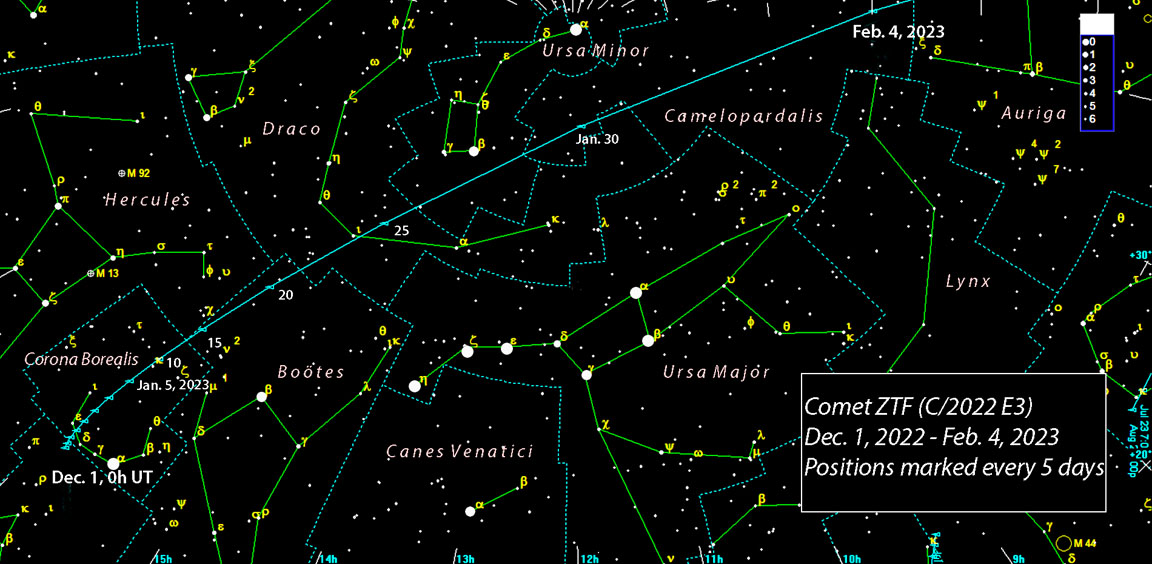

Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3)

Courtesy Emil Bonanno / MegaStar

Perihelion: January 13, 2023 — 165 million kilometers (1.1 a.u.)

Closest approach to Earth: February 2, 2023 — 43 million kilometers (0.3 a.u.)

Details: Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3) faintly glimmers at 16th magnitude right now, but hang in there: Come late November, this recent discovery will brighten up to magnitude 11 and keep on going, reaching 8.5 by Christmas.

It whistles by Earth on February 2, 2023, when it’s expected to peak at magnitude 6. I’m picturing a pretty binocular sight, with some naked-eye sightings under dark skies. From late January through early February next year, Comet ZTF will be a circumpolar object as it speeds south (6°-7° per day) and transitions from the morning to the evening sky. On the 11th, the comet passes just ½° east of zero-magnitude Mars. I can hardly stand the suspense!

Resources:

Comet Observation Database

Weekly Bright Comets

Gideon van Buitenen’s Bright Comets

Advertisement

[ad_2]

Source link