[ad_1]

FRIDAY, APRIL 1

■ This is the time of year when the dim Little Dipper juts to the right from Polaris (the Little Dipper’s handle-end) during late evening. The much brighter Big Dipper curls over high above it, “dumping water” into it. They do the reverse water dump in the fall.

■ New Moon (exact at 2:24 a.m. EDT on this date).

SATURDAY, APRIL 2

■ Castor and Pollux shine very high to the southwest after dark this week, far above Orion and lined up almost horizontally. Pollux is slightly the brighter of these “twins.”

Draw a line from Castor through Pollux, follow it farther out by a big 26° (about 2½ fist-widths at arm’s length), and you’re at the dim head of Hydra, the Sea Serpent. In a dark sky it’s a subtle but distinctive star grouping, about the width of your thumb at arm’s length. Binoculars show it easily through light pollution or moonlight, though it slightly overspills some binoculars’ field of view.

Continue the line farther by about a fist and a half and you hit Alphard, Hydra’s 2nd-magnitude orange heart.

Another way to find the head of Hydra: It’s almost midway from Procyon to Regulus.

SUNDAY, APRIL 3

■ Do you know why the Beehive cluster, M44 in Cancer, is called the Beehive? In binoculars or a small telescope, its central rows of stars suggest a traditional twisted-straw beehive (a “skep”) with a wide base and domed top. It’s more or less upright now after dark. A couple of 7th-magnitude bees emerge from its top in a little curved line. More bees swarm around.

To find the Beehive with binoculars or a finderscope, first aim at the exact halfway point between Pollux and Regulus. Then shift 4° or 5° west-southwest from there. That currently means to the lower right. That distance is almost one field-width in typical binoculars.

For more about the Beehive and its near surroundings, see Matt Wedel’s Binocular Highlight column and chart in the April Sky & Telescope, page 43.

MONDAY, APRIL 4

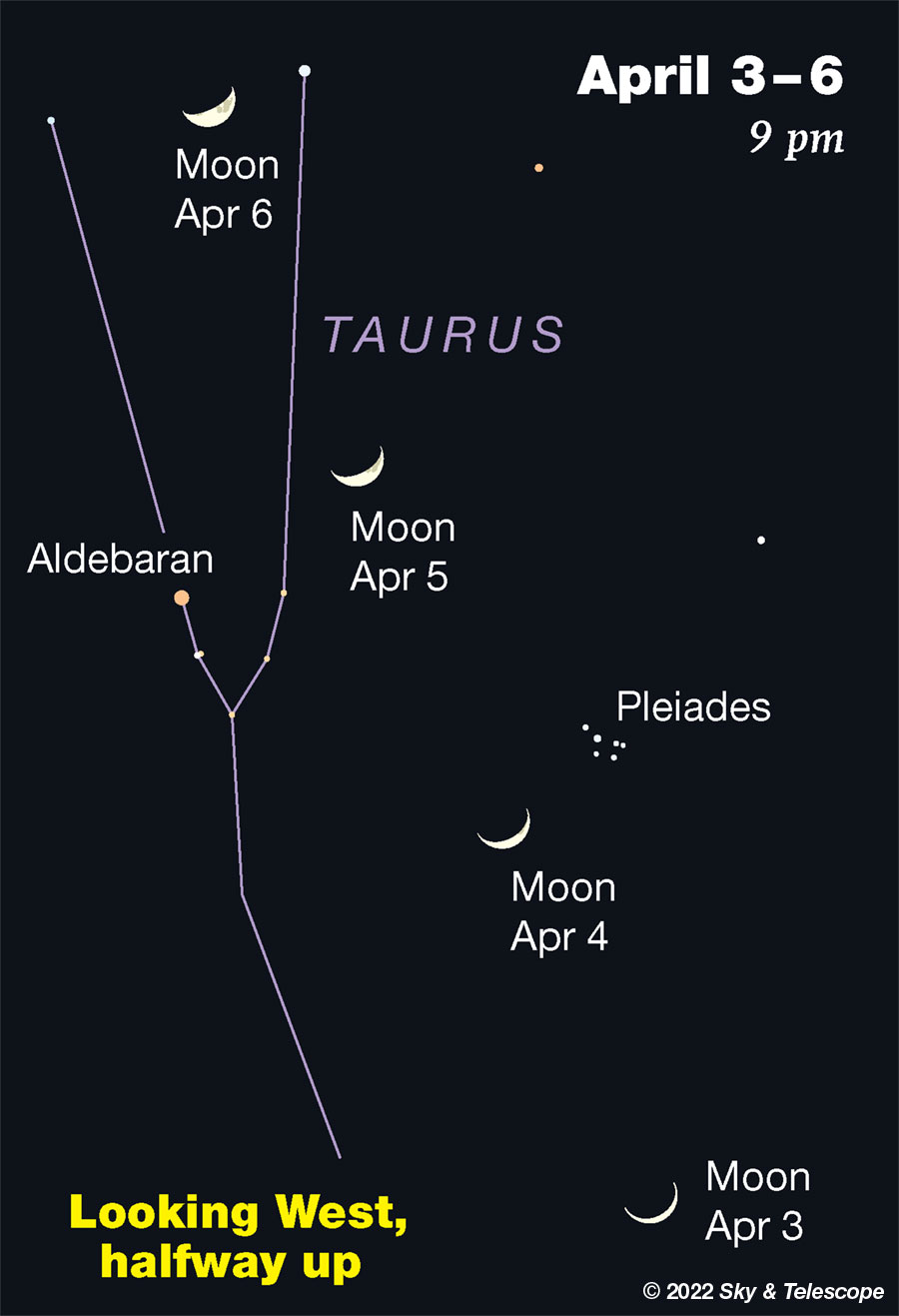

■ This evening the waxing crescent Moon hangs to the lower left of the Pleiades, as shown below. To their upper left, Aldebaran forms one tip of the Hyades’s V asterism. The V is vertical when it descends in the west in early spring, after lying horizontal when climbing up in the east in late fall and early winter.

TUESDAY, APRIL 5

■ Now the Moon hangs upper right of Aldebaran and the Hyades, as shown above.

■ Shortly after the end of twilight around this time of year, Arcturus, the bright Spring Star climbing in the east, stands just as high as Sirius, the brighter Winter Star descending in the southwest (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes).

These are the two brightest stars in the sky at the time. But Capella is a very close runner-up to Arcturus! Spot it high in the northwest.

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 6

■ Now the Moon shines between the horn-tip stars of Taurus: Beta and fainter Zeta Tauri, as shown above.

■ Capella, high in the northwest during and after dusk, has a pale yellow color matching the Sun’s, meaning they’re about the same temperature. But otherwise Capella is very different. It consists of two yellow giant stars orbiting each other every 104 days.

Moreover, for telescope users, it’s accompanied by a distant, tight pair of red dwarfs: Capella H and L, magnitudes 10 and 13. That’s about 10,000 and 60,000 times fainter than Capella itself! Article and finder charts.

THURSDAY, APRIL 7

■ Thicker and brighter every evening, the Moon now stands almost midway between Capella and Procyon to its right and left, two or three fists from each.

■ High above the Big Dipper these evenings, nearly crossing the zenith, are three pairs of dim naked-eye stars, all 3rd or 4th magnitude, marking the Great Bear’s feet. They’re also known as the Three Leaps of the Gazelle, from early Arab lore. They form a long east-west line (about three fists long) roughly midway between the Bowl of the Big Dipper and the Sickle of Leo. See the evening constellation chart in the center of the April Sky & Telescope.

In the Arabian story the gazelle was drinking at a pond — the big, dim Coma Berenices star cluster to the Leaps’ east — and it bounded away when startled by a flick of Leo’s nearby tail, Denebola. Leo, however, seems quite uninvolved; he’s facing the other way.

FRIDAY, APRIL 8

■ The first-quarter Moon this evening forms a tall, nearly isosceles triangle with Pollux and Castor above it: the two top stars of the Arch of Spring. The Moon is about 8° from each. The stars are 4½° apart.

The rest of the Arch of Spring consists of Procyon to the stars’ lower left, and Menkalinan and then bright Capella farther to their lower right.

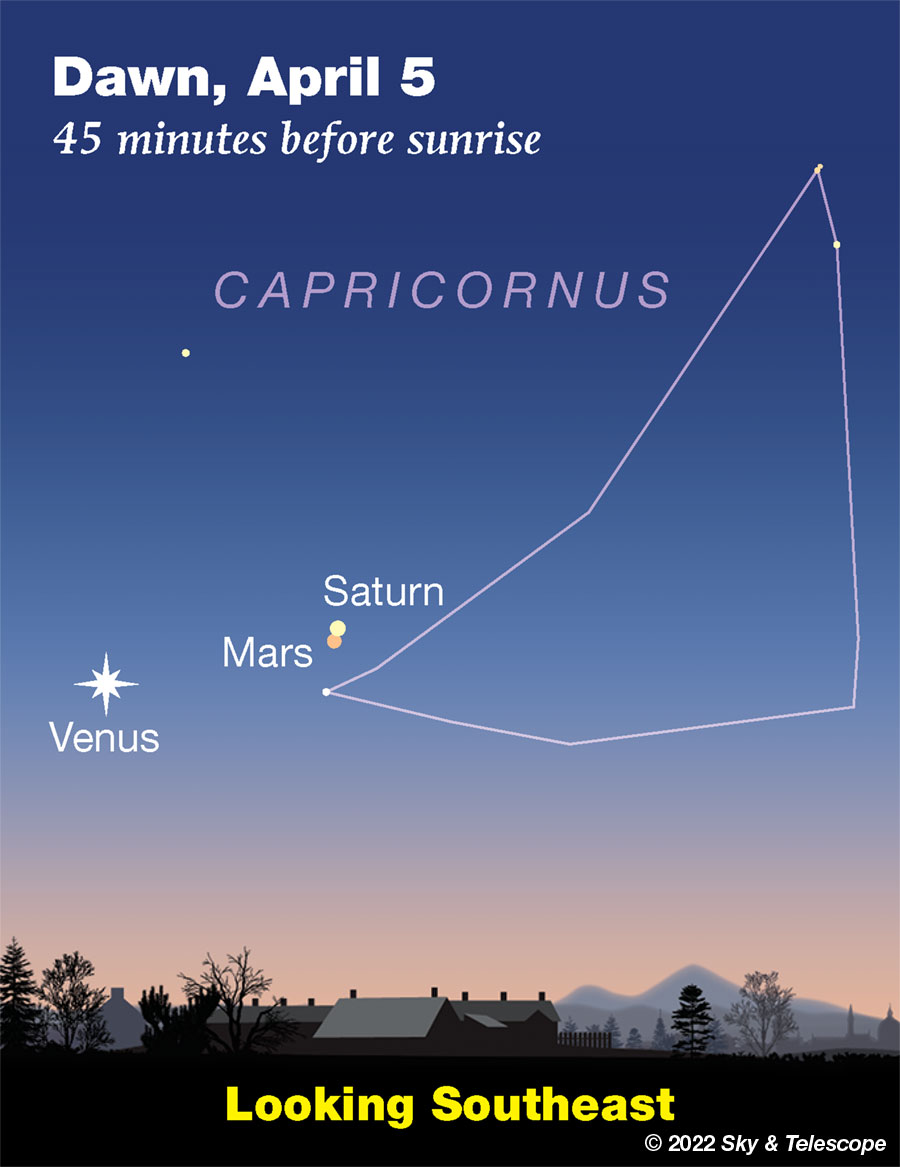

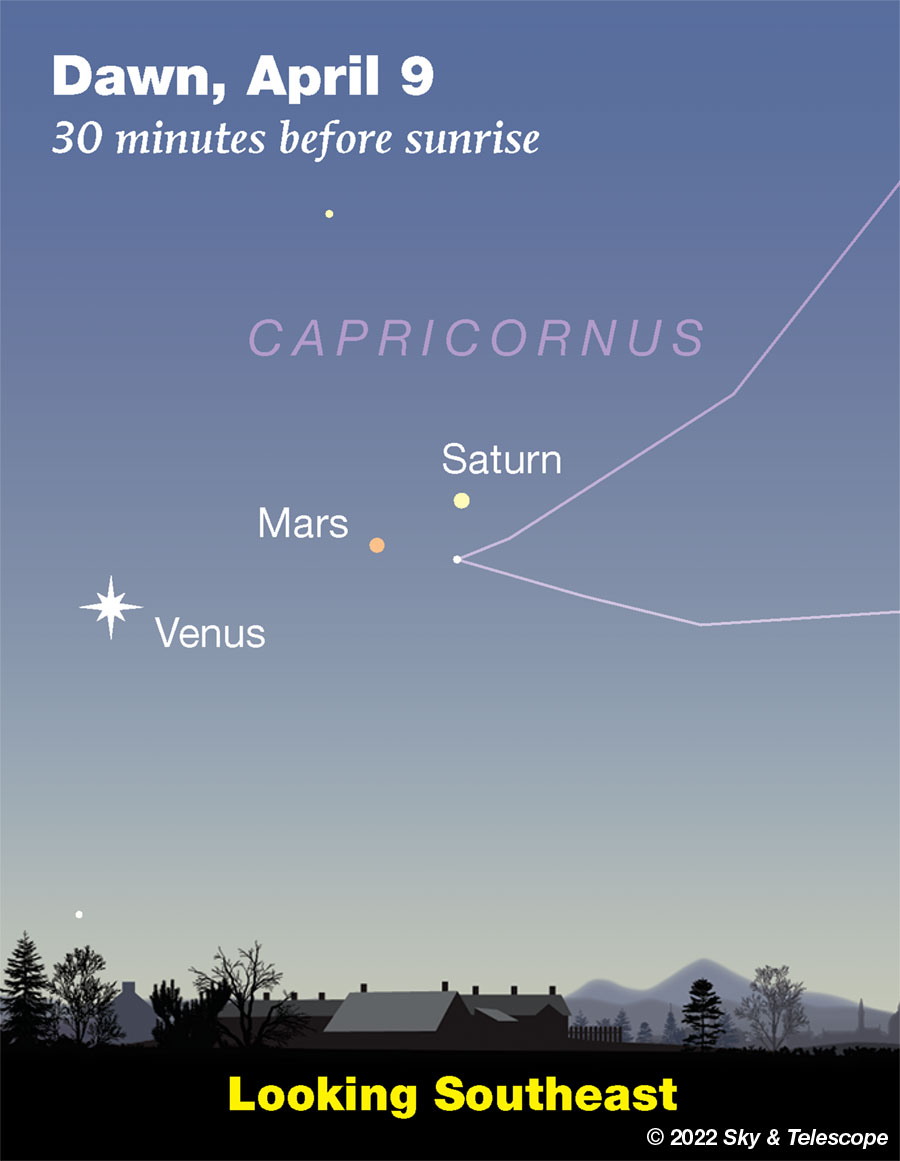

■ Over and done are the planetary triangles and bunchings that have highlighted the early dawn. Venus, Mars, and Saturn now form an expanding diagonal line, as shown below. From now on it will just get longer and longer.

SATURDAY, APRIL 9

■ Now the Moon shines left or upper left of Pollux and Castor in the evening.

■ Right after dark, Orion is still well up in the southwest in his spring orientation: striding down to the right, with his belt horizontal. The belt points left toward Sirius and right toward Aldebaran and, farther on, the Pleiades.

Advertisement

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury, Jupiter, and Neptune remain deep in the glare of the Sun. Soon, however, Jupiter will begin to reappear low in the dawn.

Venus, magnitude –4.4, is the bright “Morning Star” shining low in the southeast during dawn.

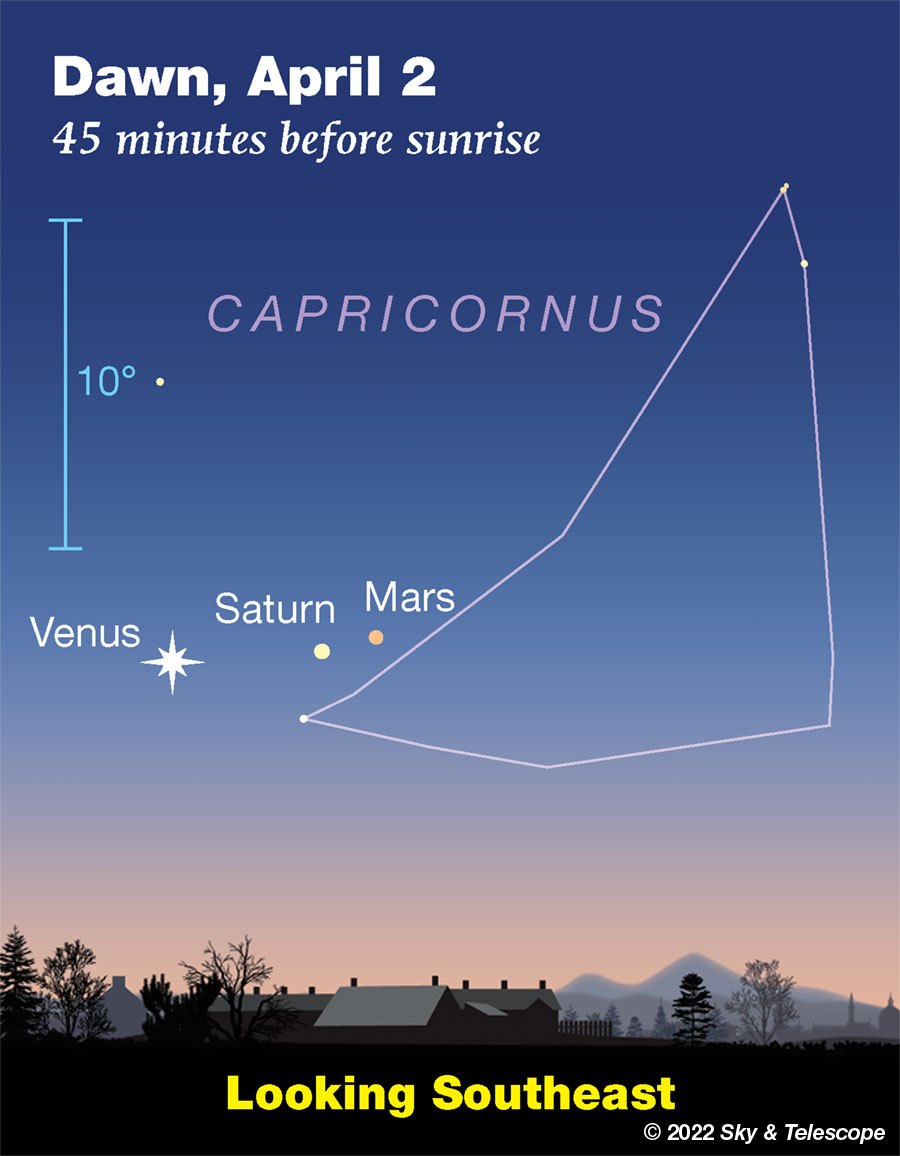

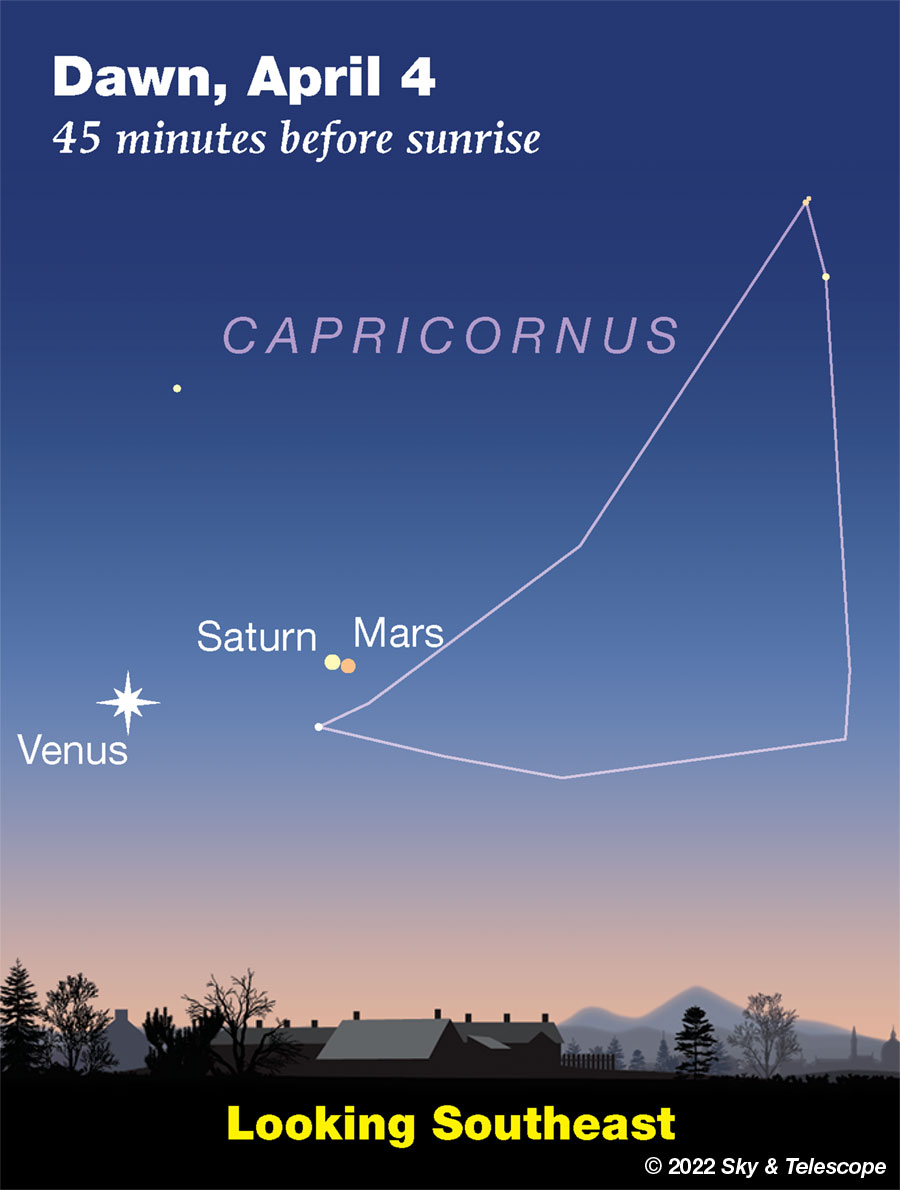

Mars and Saturn glimmer to Venus’s right. They’re vastly fainter: almost identical at magnitudes +1.1 and +0.9. Mars, however, is more orange than pale yellow Saturn.

They pass each other by about ½° on the mornings of April 4th and 5th; see the illustrations above. Bring binoculars in case dawn is getting too bright.

Uranus (magnitude 5.9 in Aries) is disappearing into the afterglow of sunset.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time, EDT, is Universal Time minus 4 hours. (Universal Time is also called UT, UTC, GMT or Z time.)

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And be sure to read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. (It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.)

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don’t think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically, meaning heavy and expensive. And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand.”

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770

Advertisement

[ad_2]

Source link