[ad_1]

Stefan Payne-Wardenaar / MPIA

Take a census of your country’s population, and you can draw up its population pyramid: a graph that immediately reveals when powerful baby booms have taken place. Astronomers have now done something similar for the stars in our galaxy.

They’ve found that the star formation rate surged some 11 billion years ago. The work also provided a detailed timeline of the early growth and evolution of the Milky Way during its turbulent “teenage” years.

Just looking at most stars doesn’t tell you how old they are. That’s why Maosheng Xian and Hans-Walter Rix (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Germany) focused on subgiants, for which there’s a neat relationship between luminosity and age. Most stars briefly pass through this subgiant phase in their later stages of evolution. While most of the hydrogen fuel in the star’s center has been converted into helium, hydrogen fusion still takes place in a thick shell around the core. The star’s resulting luminosity depends largely on its mass: Massive subgiants shine more brightly than less massive ones.

Low-mass stars can take many billions of years before they reach the brief subgiant phase, while the evolution of stellar heavyweights proceeds much faster. As a result, a census of the current subgiant population tells you their age distribution: The most luminous ones must be young, while the fainter ones are much older.

Xian and Rix selected some 250,000 subgiants from the still-growing data archive of the European Gaia space observatory, for which detailed information was available on the stars’ positions, distances, and motions. Existing spectroscopic observations from the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) in China also provided the researchers the stars’ chemical composition — in particular, the abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium (called metals in astronomical parlance).

In the March 23rd issue of Nature, the two astronomers present the results of their detailed analysis: a timeline of the major events in the Milky Way’s early history. In particular, they found that star formation rate peaked around 11 billion years ago, almost certainly a direct result of the merger between our budding galaxy and a smaller intruder nicknamed Gaia Enceladus.

Artist’s impression and composition: ESA; simulation: Koppelman, Villalobos and Helmi; galaxy: NASA / ESA / Hubble / CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

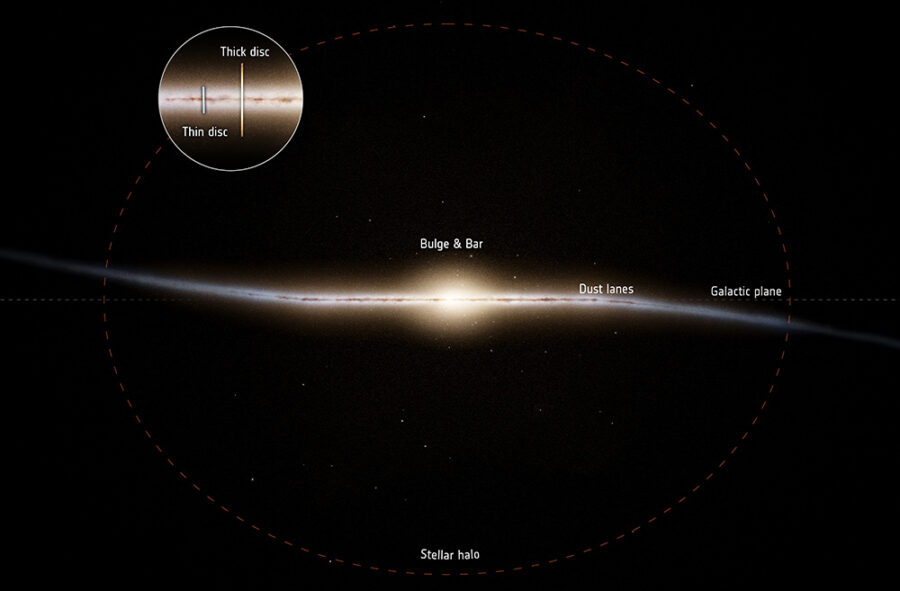

But there’s more. The data also shed light on the origin of the Milky Way’s thick disk, the fluffier pancake of older stars that’s some 100,000 light-years in diameter and 6,000 light-years thick. (Newer stars populate the thin disk, which is more like a spiral-shaped crepe only about 1,000 light-years thick).

From their data, Xian and Rix conclude that the thick disk had already started to form around 13 billion years ago, just 800 million years after the Big Bang — well before the origin of the sparsely populated galactic halo. Two billion years later, gas still filled the thick disk, and when the Milky Way merged with Gaia Enceladus, powerful shockwaves pushed the gas into forming many new stars. Star formation in the thick disk continued for another couple billion years, as primordial gas kept streaming towards the growing galaxy.

Interestingly, stars that were born in these early stages of the Milky Way’s evolution show an unexpected simple distribution of heavy-element abundance. Since supernova explosions expel heavy elements into the interstellar medium (ISM), younger stars have a higher metallicity than older ones. But for stars of the same age, the metallicity turns out to be independent of their distance from the galactic center — a surprising result, as you would expect heavy elements to slowly “sink” towards the core of the Milky Way. “[This] implies that the ISM must have remained spatially mixed thoroughly during this entire period,” the researchers write. An accompanying press release describes this as a “key result” of the new work.

Another important transition took place some 8 billion years ago. Something seems to have depleted the gas in the thick disk, and as a result star formation came to a halt. However, star birth continued in the thin disk, which is home to most of the current spiral arms, molecular clouds, and star-forming regions in the Milky Way. Xian and Rix were able to distinguish between the thick-disk and thin-disk populations by analyzing the stars’ orbits and composition.

“It’s a very nice result,” says Amina Helmi (University of Groningen, The Netherlands), whose team in 2018 identified the stellar remains of Gaia Enceladus, also in Gaia data. “By looking at subgiants, [Xian and Rix] provide a whole new perspective” on the merger event.

According to Helmi, future data releases of Gaia, which will probably be operational until early 2025, may eventually enable astronomers to fully reconstruct the Milky Way’s early history, from its chaotic origins and turbulent youth to its present sedate middle-age. “That would be great,” she says, “and it’s what I’m hoping for.”

[ad_2]

Source link