[ad_1]

Cleopatra VII, often simply called “Cleopatra,” was the last of a series of rulers called the Ptolemies who ruled ancient Egypt for nearly 300 years. Cleopatra ruled an empire that included Egypt, Cyprus, part of modern-day Libya and other territories in the Middle East.

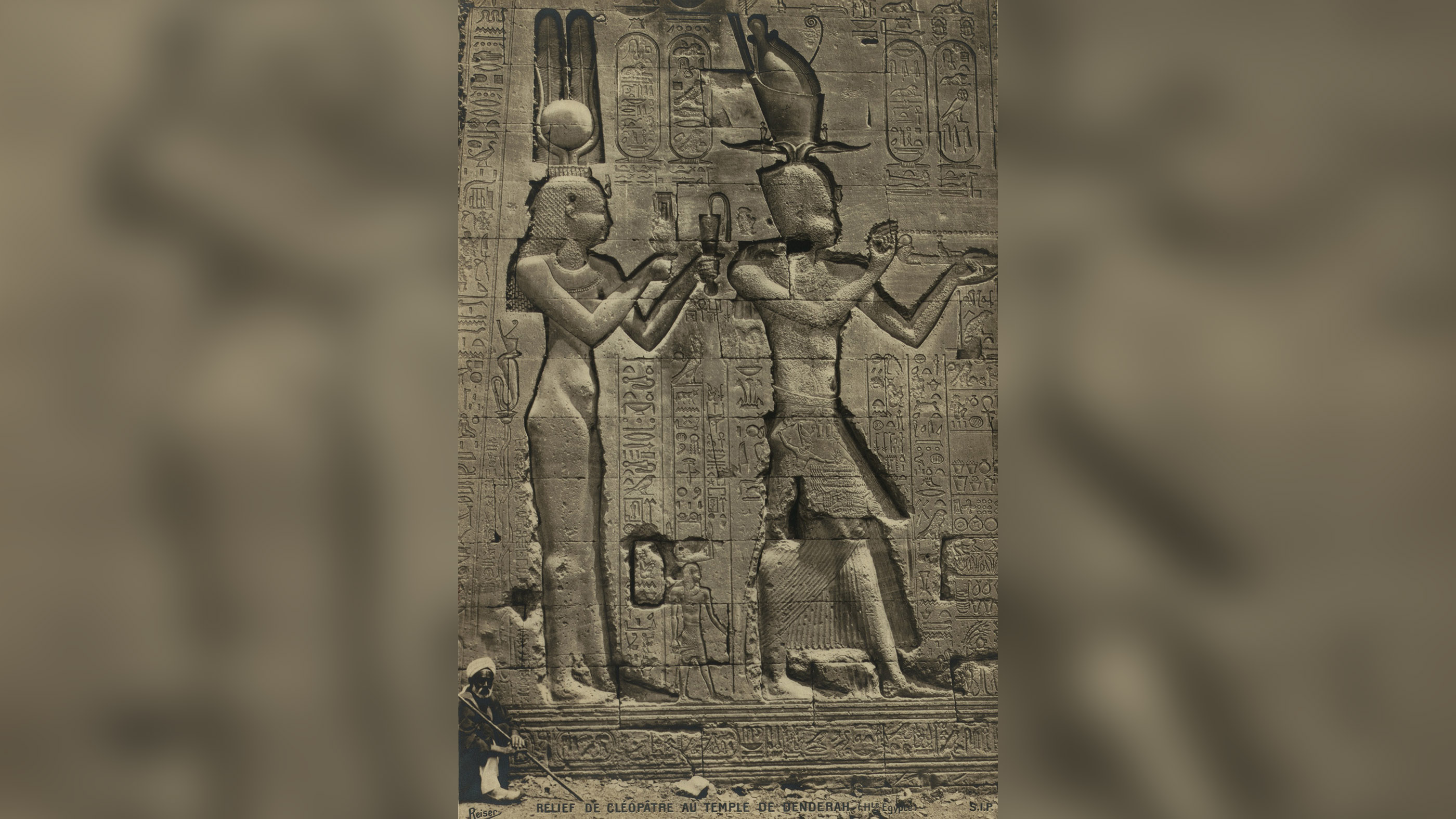

Modern-day depictions of Cleopatra VII tend to show her as a woman of great physical beauty and seductive skills — indeed, her romantic involvements with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony have been immortalized in art, music and literature for centuries. However, a number of ancient records, and historical research, tell a different story. These records describe Cleopatra as an intelligent, multilingual, female pharaoh who affirmed her right to rule Egypt and other territories.

Her “own beauty, as they say, was not, in and of itself, completely incomparable, nor was it the sort that would astound those who saw her; but interaction with her was captivating, and her appearance, along with her persuasiveness in discussion and her character that accompanied every interchange, was stimulating,” wrote Plutarch, a philosopher who lived A.D. 46-120 (Translation by Prudence Jones).

“Cleopatra was no mere sexual predator, and certainly no plaything of Caesar,” writes Erich Gruen, a professor emeritus of history at University of California Berkeley, in an article in the book “Cleopatra: A Sphinx Revisited” (University of California Press, 2011).

“She was queen of Egypt, Cyrene and Cyprus, heir to the long and proud dynasty of the Ptolemies … a passionate but also very astute woman who had maneuvered Rome — and would maneuver Rome again — into advancing the interests of the Ptolemaic legacy,” Gruen wrote.

Who was Cleopatra?

Cleopatra was born in 69 B.C. into a troubled royal dynasty. The Ptolemies were descended from a Macedonian general who had served under Alexander the Great. Although they had ruled Egypt for nearly three centuries, their kingdom was eclipsed by the power of Rome and there was a great deal of internal dissension that eventually led to Cleopatra fighting against her own brother.

Cleopatra was the daughter of Ptolemy XII and a mother whose identity we do not know. Ptolemy XII (reign 80-58 B.C.) was under a great deal of pressure from the Romans and struggled to hold onto power.

“Ptolemy XII was heavily dependent upon the Romans and as their ‘friendship’ put an increased strain upon the Egyptian economy, his rule came under increasing scrutiny from the Egyptian elite,” writes Sally-Ann Ashton, a keeper at the University of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, in her book “Cleopatra and Egypt” (Blackwell Publishing, 2008). In 58 B.C., Ptolemy XII was exiled and a woman named “Cleopatra Tryphaena” (a different Cleopatra) became ruler of Egypt, dying not long afterwards. She was succeeded by another woman named Berenice IV.

In 55 B.C., with the support of the Romans, Ptolemy XII was put back on the throne and took his 17-year-old daughter Cleopatra VII as his co-ruler. After the king died in 51 B.C., his will said that Cleopatra should share the throne with her brother (and husband) Ptolemy XIII.

Ptolemy XIII and his advisers refused to acknowledge this arrangement and fighting broke out between them, with Cleopatra being forced to flee the royal palace. It would be Julius Caesar who helped Cleopatra regain her throne.

Caesar and Cleopatra

Caesar was about 30 years older than Cleopatra, and his arrival in Egypt was something of an accident. He had been fighting a civil war against the Roman general Pompey.

After a series of defeats, Pompey fled to Egypt in 48 B.C., hoping to win support from Ptolemy XIII. The young pharaoh decided that Pompey was more trouble than he was worth and had him executed.

When Caesar landed with a small body of troops in Alexandria, he was presented with Pompey’s head — something that he was said to be unhappy about. For reasons lost to history, Caesar decided to stay in Egypt and deal with the dispute between Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra. It could be because Rome depended on Egypt for its grain supplies and a stable Egypt was seen by Caesar as being in Rome’s interest.

Ptolemy XIII tried to convince Caesar to acknowledge him as sole ruler of Egypt and barred Cleopatra from seeing him. Cleopatra, however, managed to sneak into the palace in Alexandria and successfully plead her case to Caesar, something that surprised and enraged Ptolemy XIII.

According to Plutarch she had herself smuggled inside the palace rolled up in a “bed-sack” (although this is sometimes translated as “carpet” or “rug”). An assistant named Apollodorus “tied the bed-sack up with a cord and carried it indoors to Caesar” Plutarch wrote. It’s a source of debate among modern-day historians whether Cleopatra was really smuggled into the palace like this.

“Ptolemy XIII had gone to bed that night a happy lad, secure in the knowledge that his sister, trapped at Pelusium, would be unable to plead her case before Caesar,” writes Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley in her book “Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt” (Profile Books, 2008).

“He woke up the next morning to find that his sister had somehow arrived at the palace. She was already on the most intimate of terms with Caesar and had managed to persuade him to support her cause,” Tyldesley writes.

“It was all too much for a thirteen-year-old boy to bear. Rushing from the palace he ripped off his diadem and, in a well-orchestrated public display of anger, the crowd surged forward, intent on mobbing the palace.” However, “Caesar would not be intimidated. Before a formal assembly he read out (Ptolemy XII’s) will, making it clear that he expected the elder brother and sister to rule Egypt together.”

Caesar had saved Cleopatra and returned her to power. The two became intimate and had a son known as Caesarion (although Caesar never acknowledged the child as his own). Ptolemy XIII died in a failed rebellion in 47 B.C. and was replaced as co-ruler by his and Cleopatra’s younger brother Ptolemy XIV, who Cleopatra would eventually have killed.

Being the mother of Caesar’s son gave Cleopatra greater power, and the child eventually became Cleopatra’s co-ruler.

“With a son by her side, Cleopatra VII could abandon any thought she might have had of adopting the role of a female king and could develop instead a powerful new identity as a semi-divine mother: an identity that had the huge advantage of being instantly recognisable to both her Egyptian and her Greek subjects,” writes Tyldesley.

Cleopatra had already become a goddess toward the end of her father’s reign. “But now she was to be specifically identified with Egypt’s most famous single mother, the goddess Isis.”

Antony and Cleopatra

With the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. on the Ides of March, Cleopatra found herself in an awkward position. Ancient writers say that she was in Rome when the assassination occurred and she quickly returned to Egypt.

A civil war broke out between forces led by Antony and Octavian against those who had organized Caesar’s assassination. After they prevailed, Octavian ruled the western half of the Roman Republic while Antony controlled the east.

In July 44 B.C., Cleopatra had her co-ruler and younger brother/husband Ptolemy XIV killed, and Caesarion became co-ruler of Egypt. In 41 B.C., she had her sister Arsinoe IV killed also.

In 41 B.C., after Antony took power in the east, he summoned Cleopatra to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) to question why she had not given support to his troops while they were fighting Caesar’s assassins.

Cleopatra said that she had assembled a fleet to attack the assassins but it could not reach the battlefield in time.

“Antony, struck by her intelligence as well as her appearance, was captivated by her as if he were a young lad, although he was forty years old,” wrote Appian, who lived in the second century A.D. (translation by Prudence Jones). “The acute interest Antony had once shown in all things suddenly dulled; whatever Cleopatra dictated was done, without regard for the laws of man or nature.”

Antony and Cleopatra forged a close bond and had three children together, including the twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene in 40 B.C., as well as a third child, Ptolemy Philadelphus, in 36 B.C. Antony also favored Cleopatra VII politically, ordering King Herod of Judea to hand over parcels of territory to Cleopatra.

Between roughly 40 B.C. and 36 B.C., Rome found itself at war with the Parthians, and Antony led Roman troops in the Middle East with Cleopatra sending supplies to aid him, wrote Barry Strauss, a professor of history and classics at Cornell University, in his book “The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra and Octavian at Actium” (Simon & Schuster, 2022).

Despite having children with Cleopatra, Antony was still legally married to Octavia, the sister of Octavian. In 35 B.C., Octavia, who had been living apart from Antony, arrived in Alexandria but Antony told her to go back to Rome. Octavian was upset at Antony’s behavior toward Octavia and had honors bestowed upon Octavia, something that publicized Antony’s behavior and made it awkward for him in Rome, Strauss said.

Battle of Actium

Relations between Antony and Octavian frayed and in 32 B.C., the two officially went to war, with Octavian putting much of the blame, rightly or wrongly, on Cleopatra.

The leaders in Rome “voted to pardon and praise his (Antony’s) supporters if they would desert him, and they unequivocally declared war on Cleopatra,” wrote Cassius Dio who lived A.D. 155-235. (Translation by Prudence Jones)

At “the temple of Bellona, they performed all the rites for declaring war according to custom, with Octavian acting as priest. In word, war was declared on Cleopatra, but in fact the declaration was aimed at Antony.”

Although Antony held a numerical advantage on land, the Battle of Actium was decided on the sea and ultimately by an engagement fought near Actium in 31 B.C. on the Ionian Sea. Ancient writers say that while Antony’s ships were heavier and could hold more troops, Octavian’s ships, led by general Agrippa, could maneuver better and had more experienced crews.

Before the battle, Octavian’s forces had seized Methone, a city in Greece that had served as an important logistical supply base for Antony and Cleopatra’s forces, Strauss said. This created problems for re-supplying Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet. For instance, some of Antony’s top advisers defected, and he had a shortage of rowers, wrote Strauss.

The lack of manpower and supplies meant that Antony had to burn some of his ships before the battle began, wrote Strauss, who noted that Antony was likely trying to withdraw from Actium and move his fleet to a more sustainable position when the battle occurred on Sept. 2, 31 B.C.

What happened during the battle itself is not entirely clear. From what can be ascertained from records, Octavian’s fleet used its superior mobility to swarm parts of Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet, Strauss wrote. Meanwhile, due to the lack of rowers and supplies (which meant the rowers they had were malnourished), Antony and Cleopatra’s ships struggled to conduct successful ramming attacks.

Ancient sources claim that at one point Cleopatra fled the battle and Antony soon followed with the fleet then being routed.

Death of Cleopatra

The battle sealed Antony and Cleopatra’s fate. With Octavian in control of the sea, he landed troops in Egypt and marched on Alexandria, the capital of Egypt. Although Antony managed to win a minor battle on land, he and Cleopatra were essentially trapped.

Antony, hearing falsely that Cleopatra had killed herself, decided to kill himself. According to Plutarch, Antony said of Cleopatra that “I am not pained to be bereft of you, for at once I will be where you are, but it does pain me that I, as a commander, am revealed to be inferior to a woman in courage.” He stabbed himself, though he didn’t die right away. Instead, he was found wounded and taken to Cleopatra, where he would die alongside her.

“When she received him into the mausoleum and laid him on a couch, she tore her clothing over him, beat her breast and scratched it with her hands, covered her face with his blood, called him her husband and master, and almost forgot her own misfortunes as she pitied his,” wrote Plutarch.

When Octavian entered the city, Cleopatra tried to reason with him; however, it became apparent that she would be taken to Rome and paraded as a sort of war trophy, a fate she found intolerable.

After two failed attempts to die by suicide, “she dressed herself in her richest attire, as was her custom, and settled herself next to her Antony in a sarcophagus filled with aromatic perfumes. She then put snakes to her veins and slipped into death as if into sleep,” wrote Florus in the second century A.D. (Translation by Prudence Jones).

The ancient historians Suetonius (who lived from A.D. 69 to 122) and Plutarch (A.D. 46 to 120) both claimed that Antony and Cleopatra were buried together inside a tomb. Plutarch wrote that Octavian gave orders that Cleopatra’s “body should be buried with that of Antony in splendid and regal fashion” (translation by Bernadotte Perrin).

The tomb and bodies of Cleopatra and Antony have never been found and sources have told Live Science that anything left of them is likely underwater or underneath modern structures in Alexandria.

While media reports have described claims that the tomb may be at the site of Taposiris Magna, which is located about 31 miles (50 km) west of Alexandria, most scholars told Live Science they didn’t agree with this idea. Other interesting finds at Taposiris Magna, however, include a cache of coins that bear the image of Cleopatra VII.

Fates of Cleopatra’s children

Octavian had Caesarion killed but spared the lives of the three children Cleopatra had with Antony. They were sent to live with Octavia.

While the three kids were allowed to live, the two oldest kids had to take part in a “triumph” for Octavian in Rome, where they were paraded along with an effigy of their dead mother. “Among other features, an effigy of the dead Cleopatra upon a couch was carried by, so that in a way she, too, together with the other captives and with her children, Alexander, also called Helios, and Cleopatra, called also Selene, was a part of the spectacle and a trophy in the procession” wrote Cassius Dio.

Two of the children, Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus, died in childhood while a third, Cleopatra Selene, survived and was married to Juba II, a protégé of Octavian who became ruler of Numidia, a client kingdom of Rome in northwest Africa in what is now Algeria. She brought Egyptian art as well as Greek language and culture to that kingdom.

Was Cleopatra the last pharaoh?

Although Cleopatra is often considered to be the last of the Egyptian pharaohs, we know from ancient inscriptions and art that the priests of Egypt did not believe this.

In 2010, researchers reported that a stele erected at the Temple of Isis at Philae in 29 B.C. has Octavian’s name written in a cartouche, an honor reserved for a pharaoh. Future Roman emperors (such as Claudius) would also be depicted as pharaohs in Egypt.

Although Cleopatra was dead, and her dynasty was at an end, Egyptian priests refused to let go of the idea that Egypt had a pharaoh as ruler, even though the country was being incorporated into the Roman Empire as a province.

“(The priests) had to have an acting pharaoh, and the only acting pharaoh (possible) under Octavian was Octavian,” said Martina Minas-Nerpel, a reader at Swansea University, in an interview that was published in The Independent newspaper. “The priests needed to see him as a pharaoh; otherwise, their understanding of the world would have collapsed.”

Was Cleopatra Black?

Scholars are not certain of Cleopatra’s appearance, and the question of whether she was black is an open one. The identity of Cleopatra’s mother and paternal grandmother is uncertain.

“Cleopatra was of course part Greek, but it must also be noted that the suggestion she was part African is not based on wishful fantasy alone but on the fact that we do not know the identity of the mother of Ptolemy XII (Cleopatra’s father).” writes Sally-Ann Ashton in her book.

Recently, the issue of Cleopatra’s ethnicity and skin color has been in the news as Israeli actress Gal Gadot has been cast to play her in a movie. Some members of the public have called for an actress who has darker skin to be cast instead and some are also calling for an Egyptian actress to play the queen.

Timeline of Cleopatra’s life

69 B.C.: Cleopatra VII was born.

58 B.C.: Cleopatra VII’s father, Ptolemy XII, is exiled and a woman named Cleopatra Tryphaena became ruler of Egypt, dying not long afterward.

55 B.C.: Ptolemy XII is put back on the throne with Roman help.

52 B.C.: Ptolemy XII names his 17-year-old daughter Cleopatra VII as his co-ruler.

51 B.C.: Ptolemy XII dies, and Cleopatra VII and her husband/brother Ptolemy XIII become co-rulers. Ptolemy XIII’s advisors do not approve of this and she is forced into exile.

48 B.C. – 47 B.C.: Caesar arrives in Egypt and says that Ptolemy XIII must be co-ruler with Cleopatra VII. Ptolemy XIII and his supporters revolt and are killed in 47 B.C. Cleopatra then becomes co-ruler with her husband/younger brother, Ptolemy XIV.

June 47 B.C.: After a romance with Julius Caesar, Cleopatra gives birth to their son, Caesarion. Caesar never acknowledges the child as his own.

March 15, 44 B.C.: Julius Caesar is assassinated in the Roman senate. Cleopatra VII is in Rome at the time and hurriedly returns to Egypt.

July 44 B.C.: Ptolemy XIV is killed on orders of Cleopatra VII. Caesarion becomes co-ruler of Egypt with Cleopatra.

41 B.C.: Cleopatra meets Antony at Tarsus in Turkey. The two form a romance that leads to the birth of three children. In this same year, Arsinoe IV, Cleopatra’s sister, is killed.

40 B.C.: Cleopatra gives birth to the twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios. Their father is Mark Antony.

36 B.C.: Ptolemy Philadelphus, the third child of Cleopatra and Antony, is born.

32 B.C.: Antony and Cleopatra VII are at war against Octavian.

31 B.C.: Octavian’s forces win the Battle of Actium, a naval battle that gives Octavian control of the Mediterranean Sea.

30 B.C.: Octavian’s forces capture Alexandria; Antony and Cleopatra die by suicide.

Additional resources

Bibliography

Ashton, Sally-Ann (2008) Cleopatra and Egypt. Blackwell Publishing

Miles, Margaret (ed, 2011) Cleopatra: A Sphinx Revisited. University of California Press

Strauss, Barry (2022) The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra and Octavian at Actium. Simon & Schuster

Tyldesley, Joyce (2008) Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt. Profile Books

Editor’s note: This article was updated on March 24, 2022.

[ad_2]

Source link